by Chris Hoe, Futureworx Architect

Futureworx Architect Chris Hoe is an active member of the Lilypad development team. Having curated the early concept, he supported business modelling with the wider team to understand economic viability. Following this, he worked with internal and external Stakeholders in creating the high level requirements for the overall system. Recently Chris balances broader project oversight with specific engineering tasks more closely aligned with his mechanical design background and historical experience.

Chris is an all-round mechanical design engineer with 20+ years of experience at a concept and detail design level, covering structural and fluid system parts, assemblies and installations. This has spanned a wide spectrum of applications, from broadly standalone new structures to modifications interfacing with ageing platforms.

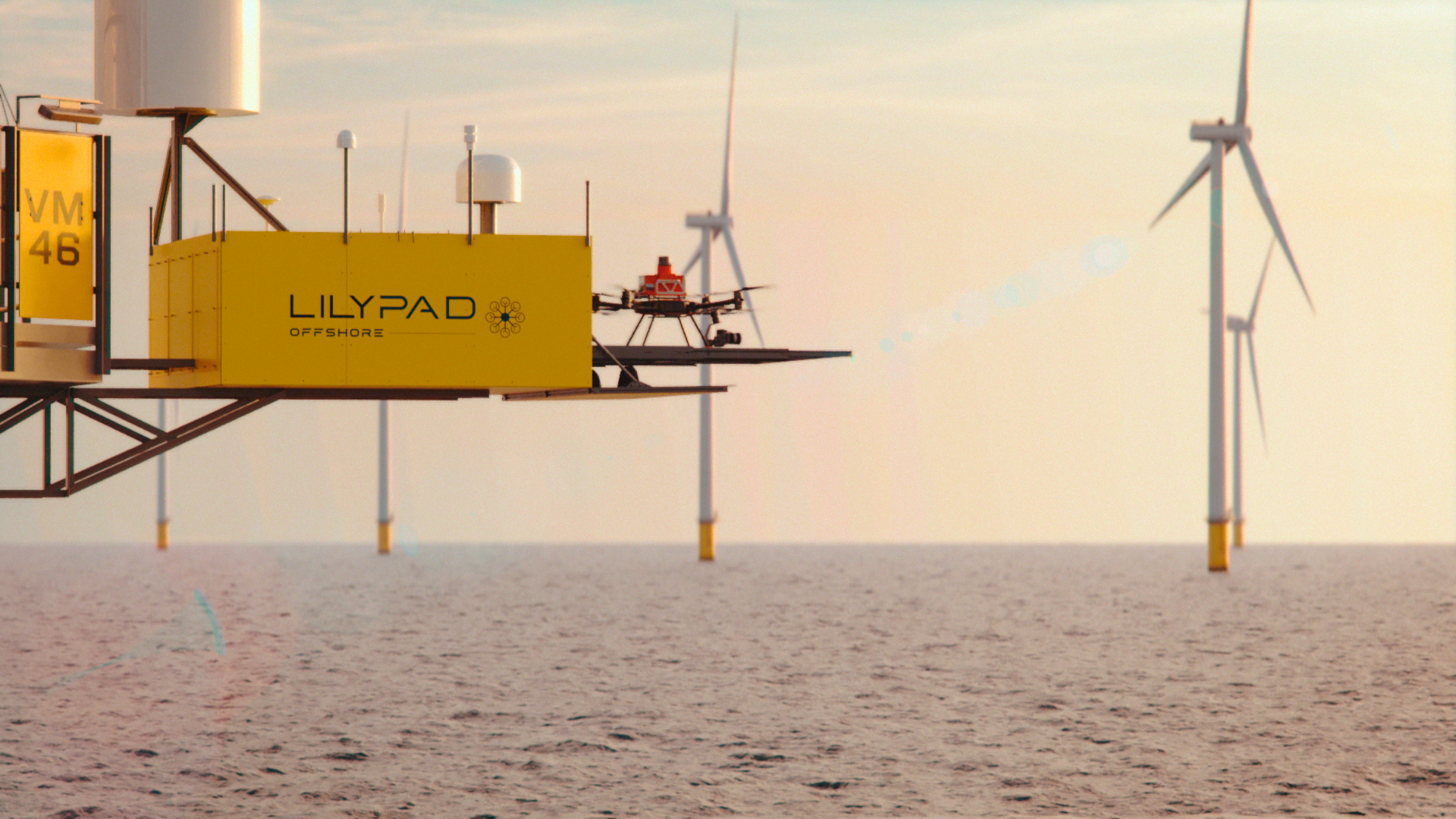

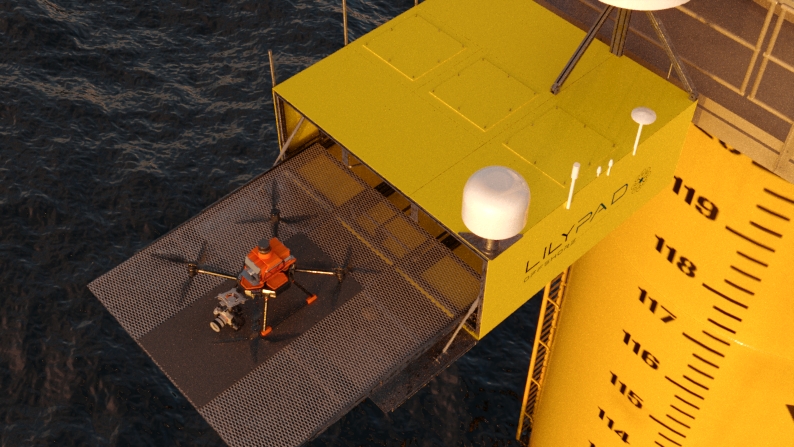

Earlier this year Marshall Futureworx announced Lilypad, our first product. Lilypad defies a simple description, but in short it is an ecosystem of resident autonomous UAVs providing—in its first application—dynamic and on-demand offshore wind farm inspection.

Since Futureworx was set up in 2021 as a blank slate, launching Lilypad just two years later takes us past a very important threshold: it’s our first idea to have graduated from concept to a fully committed product development project.

In this article I will explore that journey, describing how Lilypad emerged from our in-house process of exploring trends and creatively refining opportunities. I will also explain why going through this process gave us confidence that Lilypad is the right solution in the right place at the right time.

Tempering creativity with process

Futureworx is a young business entity. As the venture-building arm of the Marshall Group, our mandate is to explore and examine global megatrends and develop products and services that address problems of practical societal significance. By comparing the present-day and future states based on those global trends, we aim to identify promising opportunities and turn them into new ventures.

Put simply, we have been given license to explore and develop ideas ranging from the obvious to the left field. Being able to operate in this kind of sandbox environment is liberating, but finding a viable business case requires a process capable of turning blue-sky thinking into real world products—all without restricting creativity and sense of purpose along the way.

At Futureworx, our process is informed jointly by our mandate and our team culture—we like to start by thinking big and combining domains or applications, before discarding the implausible, filtering down to the practical, stress-testing potential candidates, and selecting only the most promising winners.

In practice, the first phase within this process consists of identifying problem spaces between today and tomorrow where Futureworx could potentially develop a novel concept into a solution. The second phase entails gathering together in groups to discuss and debate findings of interest, describing those concepts in enough detail to rank them against each other when assessed against a set of guiding questions.

In our first year, the trends we examined included uncrewed autonomy, energy, big data, and net zero amongst others.

Which of those mega trend explorations did the Lilypad concept fall out of? The short answer is all of them.

Distilling megatrends into a single idea

Uncrewed aviation was a logical step for us, particularly since our parent group has a long history of aerospace engineering. As well as thinking about what would be technically possible, we wanted to focus on what would be feasible from societal and regulatory standpoints.

Meanwhile, exploring trends around energy gave the Futureworx team insight into offshore wind farms and their growth predictions and potential, especially in the favourable shallow waters of the North Sea off the UK coastline. What we found is that incumbent Visual Line of Sight (VLOS) UAV blade inspection methods (e.g., a pilot on a boat with a drone, or a person on an abseil rope) did not appear to scale economically when the number of commissioned turbines rapidly increases and wind farms move further offshore.

We also identified opportunities to directly address some of the major inspection-related logistical and operational challenges facing wind farm operators. For example, inspections must be scheduled weeks or months in advance—a logistically complex undertaking compounded by the fact that a host of conditions must be favourable in order to proceed on the day. If these conditions are not met and inspections cannot be conducted, operators incur expenses nonetheless.

Researching the big data trend led our team to consider collecting, processing, and analysing large datasets. We recognised standout opportunities in wind energy inspection, specifically in terms of being able to efficiently post-process image data and identify defects or damage before they become a significant issue.

Lastly, we looked at net zero and decarbonisation, where renewable energy operations and maintenance activities in the offshore wind sector continue (somewhat ironically) to rely on high mileage movements of personnel offshore. Yet again, we saw opportunities—in this case, to remove the need for at-turbine human presence during inspections, cut back on vessel carbon footprints, and simplify logistics by reducing or eliminating competing tasks.

Turning an idea into a product

Through the process outlined above, we had sifted through trends and opportunities and isolated an idea that was starting to mature—using UAVs to improve the efficiency of offshore wind farm inspections. The next, and equally exploratory, step was to turn this embryonic idea into a viable product.

The strategic route taken by a new venture needs to be fundamentally sympathetic to the rate at which at least three factors mature: technology, society, and regulation. As a contextual example, developing autonomous urban fast food delivery drone demonstrators is achievable technically; however not all of society is convinced, and neither are the regulators. As such, approved businesses are yet to get off the ground (literally and figuratively), and face a long road ahead of them.

Futureworx team with ISS Aerospace UAV

As our idea of Lilypad started to take shape, we noticed that others in this area had been attempting to apply similar technologies to the wrong use cases or with inappropriate time-to-market aspirations—an assessment based on the society and regulation factors mentioned above.

We therefore sought to learn from these examples and stress-test our use cases by solving some challenges that could represent potential “blockers” to a future product.

First we considered some of the most obvious issues facing UAV operators: safety, privacy and noise.

Somewhere far away from built up areas is inherently safer to fly UAVs. There are few, if any, uninvolved people to get hurt in an accident, be upset about their noise, or become worried that a “bad actor” pilot is remotely snooping through their bedroom window. All of these are relevant concerns.

We felt that offshore wind mitigated the overwhelming majority of such problems, due to the remoteness of the setting, the involved nature of any surrounding infrastructure and the relative infrequency of encountering uninvolved people.

The next issue was propulsion.

Hydrocarbons, in their currently readily available forms, aren’t the propulsion fuel of the future; on the other hand, UAVs without internal combustion engines are range-limited, with battery or hydrogen tank parasitic mass clipping their wings.

We asked ourselves: “While potential operators wait for UAV propulsion technology to improve, what can be done in the near term to improve range?” The resulting idea was to use a network of staging points with shelter-like enclosures—dubbed, for ease of discussion at the time, “Lilypads.” These Lilypads would provide somewhere for a UAV to safely land, re-power, take-off and continue. Having UAVs reside within the Lilypad network on a permanent basis would allow on-demand site access by operators—while avoiding the logistical complexities, time cost and environmental burden of transport to and from site. Hypothetically, adding further enclosures to “leapfrog” along would increase range indefinitely.

Offshore wind farms again stood out as a particularly promising application for Lilypad, since turbines provide easily adaptable structures for staging points, as well as an inherently accessible electricity source from which to supply power to the enclosures and UAVs.

Through the thought processes above, we had developed an idea and zeroed in on an ideal initial application—one with a suitably remote location and a source of inherently accessible electricity, where UAVs are already used for inspections, and where operational efficiency has plenty of scope for improvement.

The idea and application had passed the stress test with flying colours.

What’s next?

The description above is intended to serve as a vignette of sorts—a glimpse into the Futureworx ideation process using our very first product as an example.

This vignette is, of course, simplified and truncated; it stops short of detailing, for example, how we worked with our partners sees.ai and ISS Aerospace to develop the final specifications of the Lilypad ecosystem, how we ensured that hardware and software fully support one another, or how we are well on the way to solving a host of challenges related to uncrewed aviation and the offshore wind setting. These topics will be covered in future articles.

Hopefully what I’ve been able to show here is that in the right environment, with the right blend of characters, backgrounds and attitude, ideation can thrive.

Ideas stop becoming wrong or right, good, or bad, but instead all serve to underpin and reinforce an iterative process by which teams coalesce upon an idea about which a story can be told, a business case be built, and a solution be engineered.

To that end, it’s worth noting that offshore wind is the ideal first application for the Lilypad ecosystem—but we certainly don’t see it as the only potential application.

The growth potential of any concept is highest when it can be shown to exist on two axes; firstly, growth within its intended or primary market, and secondly growth across different markets using the same technology.

So—where next for Lilypad? We’ll leave that up to our imagination. Watch this space.

More information on Lilypad will be available when the product is first publicly showcased during the Global Offshore Wind Exhibition in London on June 14th, 2023. If you’re visiting the show, please stop by and visit the Futureworx team on stand A66.

You can also learn more from the dedicated Lilypad webpage on our Futureworx website: https://marshallfutureworx.com/lilypad.